|

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) are playing increasingly important roles in many fields. Ranging in size from the huge Global Hawk aircraft to hand-held machines, these remotely controlled devices are growing ever more vital to the U.S. armed forces in roles that include surveillance and reconnaissance.

In some instances, UAVs must fly close to their targets to gather data effectively and may evade enemy detection with sophisticated techniques like radar stealth, infrared stealth and special camouflage. Aeroacoustics researchers at the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) are investigating an additional kind of stealth that could also be vital to these UAVs ?C technology that can evade enemy ears.

"With missions changing, and many vehicles flying at lower altitudes, the acoustic signature of a tactical UAV has become more and more critical," said senior research engineer Rick Gaeta. |

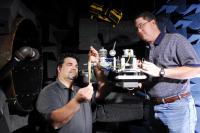

GTRI senior research engineers Rick Gaeta, left, and Gary Gray display a propeller-dynamometer device developed to test UAV aeroacoustics.

|

|

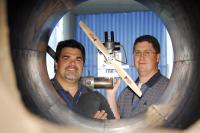

In a GTRI wind tunnel, senior research engineers Rick Gaeta, left, and Gary Gray check a propeller that has been attached to a dynamometer for testing.

|

Help could come from a field of expertise known as acoustic signature control. It's a technology that could prove highly valuable to the further development of covert, low-altitude UAV systems. The work is sponsored by GTRI's independent research program and the U.S. Department of Defense.

Gaeta, an aeroacoustics specialist, is working with a GTRI research team to find ways to reduce a UAV's sound footprint. The researchers have characterized UAV noise using both ground-based methods and vehicle flight tests.

The GTRI investigators' central task has involved characterizing the acoustic signature of a UAV's propulsion system, which typically consists of a piston engine and a propeller but could also be electrically or fuel-cell powered. The researchers needed to know how much noise comes from the engine's exhaust as opposed to the spinning propeller.

That task might seem straightforward, but real-world experiments seldom are, said Gaeta, who is working on the project with senior research engineers Gary Gray and Kevin Massey.

For instance, isolating engine noise from propeller noise is problematic. Removing the propeller from the engine also eliminates the cooling source ?C the propeller wash. But switching to another cooling source typically adds unwanted noise, which in turn complicates taking sound measurements. To operate the engine without a propeller attached, GTRI investigators had to search for quiet ways to provide both substitute cooling and a load for the engine to spin. |

Another complex testing issue involves measuring acoustic performance and engine performance simultaneously ?C a key to making the right design tradeoffs. Researchers utilized two special acoustic chambers at GTRI's Cobb County Research Facility ?C the Anechoic Flight Simulation Facility and the Static Jet Anechoic Facility.

The flight simulation facility is a unique chamber with a 29-inch air duct that can simulate forward-flight velocities while also allowing precise acoustic measurements. To take full advantage of the flight-simulation chamber, Gaeta's team built a special dynamometer capable of driving a small UAV engine and a propeller. By placing the engine-dynamometer unit in the simulation chamber, the researchers could test both engine and acoustic performance, thereby providing data for UAV design tradeoffs.

"We have been able to develop a unique testing capability as a result of this project," Gaeta explained. "It allows us to separate acoustics issues into their component parts, and that in turn helps us to attack those problems."

Investigators are also focusing on other issues, such as how to quiet an unmanned aircraft so that its own sound doesn't interfere with the task of monitoring ground noise using airborne sensors.

They want to find a systems solution because UAVs are highly integrated. For example, a concept that rendered a UAV acoustically undetectable might also affect the UAV's infrared and radar signatures. And changes in those signatures could interfere with the aircraft's ability to evade hostile infrared detection equipment. These complexities have led to new collaborations with other GTRI researchers who specialize in radar and infrared signatures.

In addition to ground-based research methods, GTRI investigators have acoustically measured UAVs in the field, where real atmospheric and meteorological effects modify the acoustic signature reaching the ground. They have acquired considerable data using GTRI owned and operated UAVs. They also traveled to U.S. military installations and made measurements of UAVs being flown there.

"We've been able to learn a lot from piggybacking on other flying programs," Gaeta added. "Those efforts have helped us to develop optimal methods for capturing UAV acoustic data and to find the best ways to process it for analysis."

Working from its findings, the research team has identified specific acoustic measures that could lead to truly covert, low-altitude UAVs.

"Our next step is to put our findings into a prototype for testing," Gaeta said. "We believe that we have the means to make tactical UAVs much quieter."

(From http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2009-01/giot-sta012209.php)

|